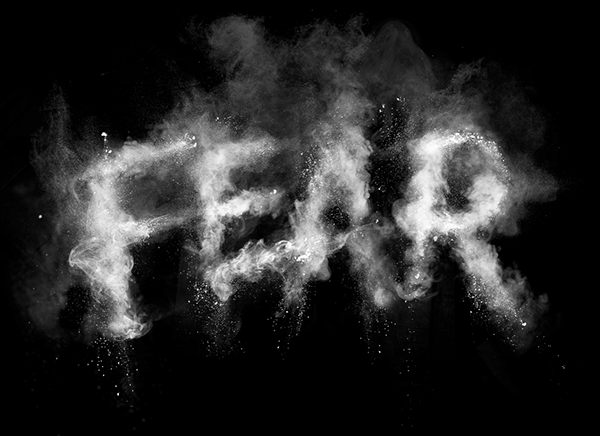

Faith and Fear

1 John 4:13-21

Faith and real life. Two weeks ago we looked at how our faith might influence the way we look at that most basic of human institutions, the family, and then last week we explored how our faith might inform our decision making – not by giving us a formula or clear, simple answers, but by pointing us towards answers to two key questions – what sort of person would God have me be and what sort of things would God have me value.

Today we turn to the question of faith and fear. And once again, and I guess you’re not going to be surprised by this, I going to have to say that I don’t think there are any really simple answers.

Of course, there are many who would disagree. Google “what does the Bible say about faith and fear” and you’ll find all sorts of websites that very confidently proclaim that the Christian should never be afraid. Of anything. Gotquestions.org simply declares, in the opening words of their article on the topic that “faith and fear cannot exist together” (I have to admit I didn’t read very much further).

And on one, pretty superficial level, you can see why that might be. The command “fear not” is, after all, one of the most common instructions given to people in the Bible. So doesn’t it make sense to say that not being afraid is an important part of our faith?

Well, no. Or at best, yes and no.

Because the command “do not be afraid” mostly arises in two contexts in the Bible. The first is when someone comes face to face with God (or, more frequently, with an angel), and they are, quite naturally, terrified. “Fear not”, the angel said to Mary, to the Shepherds, to many of the prophets. So one thing we can probably reasonably conclude is that if we come face to face with a spiritual representative of God, we need not fear them. OK. But maybe not the most immediately applicable to day to day life.

And the other context is when God is asking someone to do something that seems to be crazy or dangerous. “Fear not, for I am with you”, God declares to the prophet Isaiah. “Do not be terrified for the Lord your God will be with you” God assures Joshua, as he takes on the leadership of the people.

And although, once again, the case of God specifically calling an individual to a dangerous or uncertain path may be the exception rather than the rule, here at least is the start of an idea more valuable, more general. “Do not be afraid, for I am with you”. As we reflected last week, in our decision making, our guidance by God is often much more general, more nebulous, more guided by wise principles than direct orders; but I don’t think that invalidates the promise. The promise is rarely (if ever) “I will be with you as long as you make the right decision”. Instead it is “nothing can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus”.

Having placed that as starting point, I think it’s helpful to explore four rather different sorts of fear. Because the more you think about fear, the more it becomes clear that it isn’t a simple, single thing. So I’d like to briefly think about how we respond to the natural fear of danger, to fear of the unknown, to fear for the future, and to fear of God.

So let me start with the natural fear of danger. A Biblical scholar once said to me that a rule of thumb that she used when interpreting any Biblical text was this: if your reading leads you to see God’s teaching as less loving or less wise that the things you would teach your children, then you need to rethink how you are reading the Bible. So if you read a Biblical text in such a way as to argue you shouldn’t be afraid of cars when crossing the road, or of brown snakes when walking through long grass, then you’ve probably missed the point. There is a natural fear of things which are actually dangerous to us that we learn, and that we need. It’s a problem, of course, if such fear debilitates us, but the counter to that is surely “fear appropriately”, not “fear not”.

This sort of fear protects us – and at it’s best, it inspires us to protect others as well. It is good fear.

The second sort of fear I wanted to explore is fear of the unknown – fear, especially, of the stranger. And this is interesting because in some psychological ways it is closely related to the first: we are, it seems, hardwired to fear that which is strange, that which is unusual, different. And that makes a lot of sense in a lot of ways – there is a great evolutionary advantage to not, for instance, carelessly eating something you’ve never eaten before. It might be fine, but the downside of eating something poisonous is much worse than missing out on something good. The known is just that – known, known to be safe, or to be avoided. The unknown might be dangerous or not, but the safest course of action is to fear it just in case.

But our problem is that our instincts still operate even when we know, in some rational part of our mind, that they should not. So our fear of the unknown gets applied to fear of those who speak a language we don’t know, those who look different from us, those whose cultural practices are different, those whose sexuality or gender identity are different from ours.

Listen to some of the rhetoric about Islamic immigration: “of course,” people will say, “not all Muslims are terrorists” with the clear though often unspoken bait of fear: “but can you be sure?”

I’ve mentioned before, that one of my favourite word plays in Greek is the word translated “Hospitality” – xenophilios – which is made up of the two words ‘xenos’ – the other, the stranger, the foreigner – and ‘philios’ – brotherly love. Hospitality is extending family love to the stranger. In the book of Hebrews the author challenges us “Do not forget to show hospitality to strangers, for by so doing some people have entertained angels without knowing it.”. The fear of the risk of the unknown is turned on its head – love the stranger, because of the amazing possible upside…

A third form of fear is the one spoken of famously in Psalm 23 – though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will not fear. The valley of the shadow of death, or “of darkest shadow” is a place of fear. Fear for the future. Fear of death. Fear of loss. But the psalmist responds with a declaration, an assertion: “I will not fear”. Of course, hearing someone assert that they’re not afraid, that they won’t be afraid, is a pretty clear signal that they are, in fact, or expect to be, precisely that.

But the assertion signals a choice, and a declaration of confidence: “I will not be afraid, because you are with me”.

And here, as I indicated before, I think we come closest to those many occasions in the scriptures in which God says to those God has called that they need not fear, for God is with them. Part of what I think makes Psalm 23 so powerful is that, not only does it not deny the reality of the valley of darkest shadow, but it also does not paint fear as a failure or a lack of faith. The psalmist’s “I will not fear” rings through not as criticism of those who fear, but as an invitation to see differently, to see from a different perspective. An invitation to place our fear alongside our confidence in God. An invitation to speak to our fears, to declare to our fear “my God is with me”.

Like the child facing a bully and declaring “I am not afraid of you” – even though it isn’t true, somehow, sometimes, just the act of saying it makes it a little bit truer.

So so far we have justified, natural fears that I’m suggesting are healthy, fear of the unknown which is equally natural but which we are invited to push through to see the positive possibilities in the stranger, the fear of the darkest valley which we still feel even as we declare that it is not so… so maybe it’s good to know that the last of our four fears is one I really believe we can put aside.

Fear of the punishment of God.

And there is a definite strand of Christian theology, Christian teaching, that leans very heavily of this fear. My son came home from school one day saying that his scripture teacher had told them that their friends who didn’t believe in Jesus were going to go to hell – he was in year one at the time. Jonathan Edwards famously preached the sermon “Sinners in the hands of an angry God” calling his listeners to repentance based on the fear of what would befall them if God’s wrath was fully felt. And how many generations have grown up with the image of God watching over them, waiting to catch them doing something wrong.

Fear, the author of 1 John writes, has to do with punishment. But he does not write to inspire such fear; rather to set it aside; that we might have boldness, he writes, on the day of judgement.

“There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear; for fear has to do with punishment”. The implication is clear: because of the love of God, there is no need to fear any punishment.

Which is really where I want to leave the fear of God. There is plenty in the Bible, especially in the Old Testament, that would paint God as to be feared, and would portray obedience to, service of, God as something you do, at least in part, to avoid the wrath that befalls those who do not toe the line.

And you hear the same sort of attitude often enough today, especially if you make the mistake of reading the comments on Facebook posts.

But we read the Bible through the lens of Jesus, and as people who have been told that we are children of God.

So to paraphrase my friend:

If your reading of the Bible leads you to see God as less loving towards you than a good parent is towards their children, then you need to rethink how you are reading the Bible.

Amen