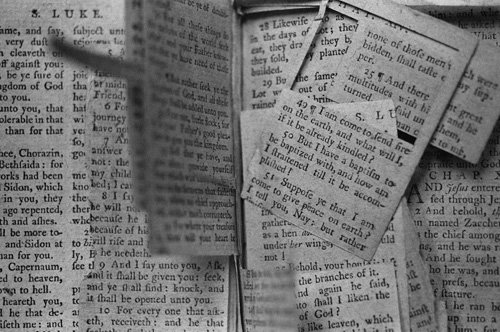

Selective quotation

Luke 4:14-21

We in the Church have, I think it’s fair to say, a complicated, ambiguous, relationship with the scriptures.

We know them as the story that shapes our worldview, our perspective on life, but find much in them that jars with our experience: a creation story that bears little relationship to the evidence of science, a set of laws designed for a mono-cultural, religious state almost entirely unlike ours, a history that seems to mix mythical and historical elements without any distinction being made.

And we turn to the scriptures for moral and ethical guidance, and find the profound insights of the people of God in the voices of the prophets – ‘what does the Lord require of you, but to act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God’ the words of the law ‘I am the Lord your God, you shall have no other Gods before me’, and of course, in the sayings of Jesus ‘Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you … do not judge, so that you may not be judged’. But alongside these words which challenge and inspire us we also read of God’s command to genocide: ‘When the Lord your God brings you into the land that you are about to enter and occupy, and he clears away many nations before you and you defeat them, then you must utterly destroy them. Make no covenant with them and show them no mercy.”

We have a complicated relationship with the scriptures. For some believers it seems to be simple – the scriptures are to be read and accepted as given to us, and any difficulties we have are problems with us, not with the text. And while there can be great humility in such an approach, it doesn’t seem to me to do justice to the very human nature of these writings, and to the simple impossibility of encapsulating God in words – a God who could be truly described in human language would not be a God worthy of worship.

And yet we cannot escape from these words. For they are the story that has formed us into the people we are, the story that continues to form us.

And at crucial points in the history of God’s people, it has been these words that have guided them, defined them, called them to be the people they really were.

Even the people of Israel had a complicated relationship with the scriptures. For though the words were human and the editing and compilation relatively recent, the tradition, the spirit, the vibe of the thing, rang true. It was their story, their law, their scripture.

And that telling of the story, compiled in exile, were the words that were handed to Jesus in the synagogue. This was the story that he grew up with, the story that shaped the community his family lived within.

If you read Jewish writing of the day you find debates much like those in the modern Christian world – arguments over which stories were history, which were allegorical, which were poetic. That sort of debate was alive and well in the first century, it’s not a modern invention. The modern invention, if there is one, is treating the Bible as if historical literalism was all that mattered, as if fact was a synonym for truth. There’s a phrase used in Godly Play, in response to the question ‘is this story true?’ which I rather like: ‘all these stories are true. Some of them actually happened.’

The people of God have always had a complicated – and I think it’s fair to say, creative, relationship with the scriptures.

So let me read to you the words of Isaiah 61, the passage Jesus chose to read from that day in the synagogue, at the start of his ministry:

The spirit of the Lord God is upon me,

because the Lord has anointed me;

he has sent me to bring good news to the oppressed,

to bind up the broken-hearted,

to proclaim liberty to the captives,

and release to the prisoners;

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour,

and the day of vengeance of our God

It’s a game of spot the difference. There are a couple of places where the words that Luke reports Jesus as reading differ slightly from the words recorded in the book of Isaiah, but the most striking are words that Jesus didn’t say, words he chose to omit. That when he reaches the dramatic summary:

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour,

and the day of vengeance of our God

he stops in the middle of the thought:

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour

and omits the second half

and the day of vengeance of our God

As if to say “yes to the year of the Lord’s favour, but not so much to the vengeance of our God”.

To the mainstream of Hebrew thought, the two ideas, the time of God’s favour and the time of God’s vengeance, were inseparable. God’s favour was all about the vindication of the people of God, the setting free of the oppressed Hebrew nation, by the throwing down of the oppressor, God’s judgement on those who are not of the faith.

You read it in the works of history and the prophets; “Lord save me, cast down and trample upon my enemies” is a pretty simple paraphrase of a high proportion of the Psalms (although we tend to be a bit selective in our reading).

These were, as it were, two sides of the same coin. God’s people would be vindicated by the downfall of the other. And it takes very little imagination or observation to see the same dynamic at work in much of the religious and political thought of our day: we will win by the casting down of our enemies.

But Jesus takes this scripture and reads it to them, fresh from his time of reflection, prayer and introspection in the wilderness, right at the start of his ministry, and he stops right in the middle of the thought; proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.

Just as he will in his teaching: “You have heard it said…. but I say to you…” “You have heard it said, love your neighbour and hate your enemy, but I say to you ‘love your enemy’” Jesus’ embrace of his tradition is strikingly selective. As if to say, “I will have all of column A, but none of column B.”

In Luke’s telling of the story, these are the first words in which Jesus defines his ministry. This is Jesus’ mission statement, his description of the Kingdom of God that he has come to proclaim. And he pointedly chooses to cast his vision, his mission, his work, in the positive.

When Jesus went to the outcast, the poor, the leper, the foreigner, the sinner, he was making real these words: God sent me to let the oppressed go free. When he declared forgiveness to those held imprisoned by their guilt and shame, he was proclaiming release to the captives. In his healing, literally, and his teaching, figuratively, he was proclaiming the recovery of sight to the blind. Even when he challenged the rich and powerful, he was declaring good news to the poor. In every act of grace, love, and forgiveness, he was proclaiming the Lord’s favour. That was what he was about. His mission, his work, found shape in this scripture.

‘Today’ he told them ‘these words have been fulfilled in your hearing’.

When you read Isaiah, it’s always hard to tell whether the prophet is speaking of an individual or a community, a contemporary figure or one who is still to come. Jewish scholars then, and Jewish and Christian scholars now, will argue the point. But as I hear the words of Jesus, I don’t hear him saying “Isaiah was talking about me.”. I don’t hear him saying “Isaiah was looking forward to what I would do”. I hear him saying “Isaiah had insight into God’s heart, and I am going to make it happen. I am going to make these words real. I am going to allow the vision of Isaiah to shape me. I will proclaim – and not just proclaim, I will make real, the year of the Lord’s favour”.

But at the same time, there are part of Isaiah’s vision that Jesus does not embrace. And in Jesus’ selectivity, his rejection for the need for vengeance, his refusal to buy into the narrative that says that for “us” to be favoured “they” must lose out, lies perhaps the most powerfully counter-cultural part of his message.

Counter cultural then

Just so much, if not more, now.

The Lord’s favour need not have a dark side.

Amen