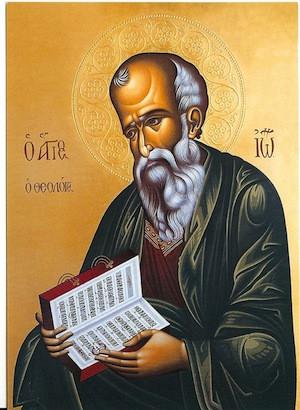

John

John 1:1-5 | 1 John 4:7-21

As we draw towards the end of our series on learning from the followers of Jesus, and towards the end of the Church year – it’s advent in just two weeks – and we come to the witness of John.

Four books of the New Testament bear the name of John – the gospel, and three short letters (it’s generally accepted amongst Biblical scholars that the book of Revelation, which also carries the same name was written by a different ‘John’).

But the gospel and the three epistles seem very likely to have been written by the same author over a period of ten or twenty years, towards the end of the first century.

Traditionally these books were believed to have been written by John the Apostle, the disciple of Jesus. In which case he would, at the time of writing, have been an elderly man – having witnessed the events of Jesus’ ministry in his late teens or early twenties, he would have been recording them in his 80’s or 90’s. Of course, he’d spent the seventy years in between telling the stories over and over again, as a leader of the Church in Ephesus.

If not actually written by John, its very likely that they were written on his behalf and in his name by someone who learned the story of Jesus at John’s feet, someone from his Christian community. Either way, there is broad acceptance that these writings represent the teaching and tradition of John.

So whether the author was John or someone who heard the stories over decades from him, the Gospel of John and the Epistles of John, though written later than the other gospels and the Pauline epistles, in many ways bring us closer than any other Biblical texts to the actual person of Jesus – for John, with Peter and Andrew, formed the inner circle of Jesus’ friends, the three who were with Jesus even when the rest of the twelve were not, at the transfiguration, at the raising of the young girl from death.

And what John gives us, in all of his writings, is not a blow by blow account of the life of Jesus, in the style of Mark, nor a polemic in the style of Matthew or Luke, nor a carefully constructed argument like Paul.

More than any other writer of the New Testament, John writes as if what he has to say, what he needs his reader to grasp, to feel, to experience, is beyond the simple meanings of human language to capture – for he is writing about God, how could it be otherwise, God cannot be captured in simple propositions, statements which are well defined and unambiguous and true.

What John gives us is theology as poetry.

Indeed, reading John’s gospel makes me wonder whether it’s even possible to write theology as prose.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.

It’s one of the more famous texts of the Bible for good reason: it layers imagery and truth together – the Word, and God, creation, light, darkness, humanity – in ways that speak to us far more deeply than propositions and thesis and arguments. How could God entering the world ever be reduced to a creed or doctrinal assertion?

Instead this great miracle, this deep mystery of the faith, is painted in the language of imagery. en arche, “In the beginning”, the opening words of the Hebrew scriptures, en arche en ho logos, “was the Word”, an image of creative power borrowed from the Greek philosophers; and the Word was God – the power revered by the Greeks and the God worshipped by the Hebrews declared as one.

John knew Jesus. He knew him as a man, as a friend, as a teacher; but at the same time he knew him as the Word, as the Life, as the Light that shines in the darkness, that the darkness has never overcome.

He doesn’t try to explain; he paints a picture of Jesus and invites us to admire – or rather, invites us to fall in love.

And most of all, what John, this man who knew Jesus as well or better than any other, gives us is a touchstone for our faith; a central image against which we hold up all other images of God; an idea alongside which other ideas can be measured.

God is love, and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them.

John wrote at a time when doctrinal debates were beginning to take hold within the Church, arguments about whether Jesus was a real person or a divine spirit in human form; arguments about the value or otherwise of the physical life; arguments about whether right beliefs or right practice were the true marks of the follower of Jesus; arguments about who had Christ’s authority within the growing Church to rule on all such matters.

And John’s response, for the most part, is not to weigh in to these debates so much as to draw his readers back to this touchstone, to invite us, as fellow followers of Jesus, to place our arguments and practices up against the standard of God, which, he declares, is love:

Beloved, let us love one another, because love is from God; everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love.

Love is from God

Love is knowledge of God

Love is God

And that love that is God is revealed to us:

God’s love was revealed among us in this way: God sent God’s only Son into the world so that we might live through him. In this is love, not that we loved God but that God loved us

And so our standard of faith, of behaviour, even of belief; the only standard that makes sense, the only measure against which everything can be held up for comparison is this: the love of God revealed to us in Jesus Christ.

What John has to teach us about living as a disciple really is as simple as that.

Honestly, quite hard to stretch out into a sermon.

let us love one another, because love is from God

There it is. From someone who knew Jesus better than anyone.

But John has one more thing he wants to say about love, one thing that he wants to be so clear about that he drops out of poetry into a simple assertion and commandment:

Those who say, ‘I love God’, and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars; for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen. The commandment we have from him is this: those who love God must love their brothers and sisters also.

It’s too easy to declare you love God, and, on the basis of that self-proclaimed love of God, treat others terribly.

Because they don’t understand God the way you do.

Because they live in a way that doesn’t match up to your understanding of God.

Because they make you uncomfortable.

Because they don’t fit in.

Because to love them might require you to make sacrifices of your wealth, your comfort, your luxury.

John doesn’t seem to have a lot of sympathy for this sort of sophistry: Those who say, ‘I love God’, and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars

Tell us what you really think, John.

So what we learn from John, this first follower of Jesus? Things we already knew, but always need to be reminded of. Things that form the heart of the Christian way:

God is love;

We love because God first loved us;

If we love God, we must love one another.

Amen