What do we do with the passover

Exodus 12:1-13 | Luke 22:14-20

So welcome to an episode of “what on earth are we going to do with this story”.

A story in which we are told of God committing an act of terrorism. Systematically killing the firstborn of every family in an entire nation, in order to get the political leadership to change their direction.

However great the injustice, however wrong it was that the people of Israel were being held as slaves by the Pharaoh, it seems to me unimaginable that such an action, in human hands, could be justified. We would call it a war crime – the deliberate targeting of non-combatants, in many cases children, people who had no power in Egypt, no influence with the Pharaoh, no responsibility for what was being done.

So what are we to do with it?

We could, of course, ignore it. Put in that basket with all the other bits of scripture that we could really struggle with but would rather not. There are plenty of other bits of the Old Testament (in particular) that we choose to do that with.

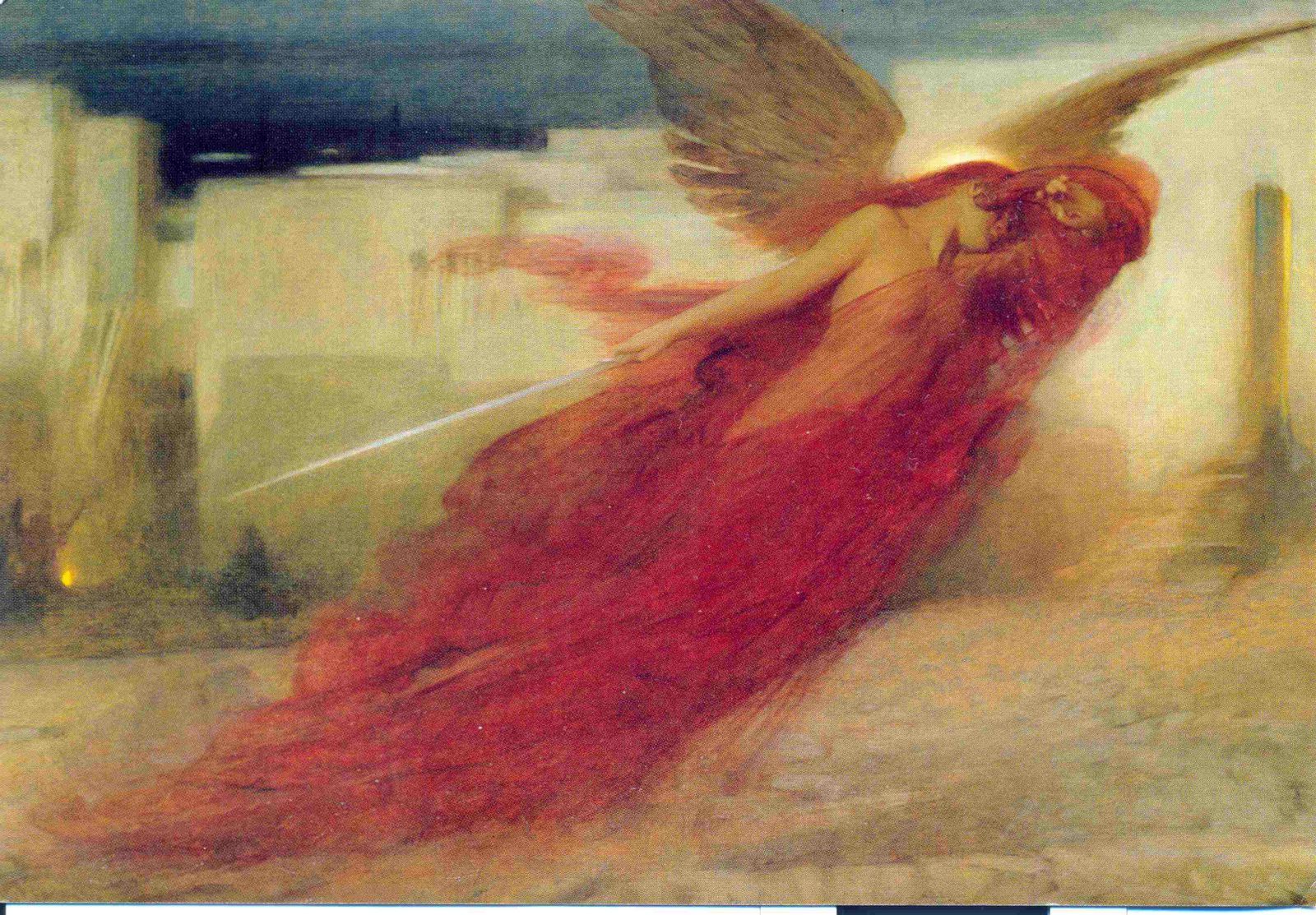

But this story is harder to ignore. Because this story, the story of the Exodus and of the meal prepared by the people of Israel as they get ready to flee from Egypt in the aftermath of God’s slaughter, lies at the heart of the most significant religious festival of commemoration in the Jewish calendar – the Passover is even named for the way that the angel of death passed over the homes of the people of Israel – and that Passover meal lies at the heart of our most enduring Christian sacrament, communion.

So what are we to do with this story?

Well we might start by reflecting on the story came to be told.

It’s pretty widely accepted that the stories recorded in the books of the

Pentateuch, the first five books of the Bible, were preserved in an oral

tradition for many generations. Old Testament scholars generally hold that

there were, in fact, a number of independent oral traditions of the same

stories, each holding currency with different parts of the community – this is

why quite a number of stories seem to be told multiple times with different

details, or why sometime a single telling of a story seems to be internally

inconsistent, where details from more than one tradition have been combined

into a rough consensus telling.

And it’s generally recognised that the Pentateuch came into their current form during the time of exile in Babylon; generations after the collapse of the Kingdom of David and Solomon, when the people of Israel were, once again, captives in a foreign land, far from home.

Our first step in coming to terms with the violent image of God in this story is this: to remember that these were the words of the powerless.

And obviously this goes a long way to explaining the great emphasis placed on the story of the Exodus – the memory of a time long ago when the people had been forced from the land, taken into slavery, but then rescued by the miraculous works of God, set free to once again be the people that they were called by God to be.

And it explains, too, the fact that the people of God were quite

willing to include rather bloodthirsty details in the way they remembered and

told the story; for people oppressed by military might and by violence, the

idea of a military God, setting them free by superior violence, is

understandably attractive (even if, from our perspective, ethically suspect).

It’s no coincidence that the story of the Exodus was one of the most loved and preached on by African American slaves in the southern states of the USA; it’s a story with great appeal to those who are powerless, but who hold onto faith in a God who is mighty to save.

And in a similar way, the festival of Passover and the story of the Exodus was very powerful in the memory of the people of Israel in Jesus’ time; another point in history where the Jewish people were, although not in exile, under the military power of a vastly superior empire.

And here we can take our next step: because for once, in this case, we can ask the question “What would Jesus make of this story? What would he do with it?”; because we have the record of just how Jesus chose to use the story of Passover.

For Jesus knew it was a story of redemptive violence, a story in

which violence – God’s violence – was the pathway to freedom. And he didn’t, as

we are tempted to, pretend that the violence wasn’t there, he didn’t gloss over

the violence of the story.

Instead he did something far more radical. As part of a marginal and threatened group within an oppressed and captive people, he took a narrative in which violence was the pathway to freedom, and he made himself the object of that violence.

In keeping with his consistent record of preaching peace, preaching love of enemy, Jesus refuses to take this story of violence and apply it, gleefully, as so many did, to the oppressor; instead, knowing that the violence was inescapable, he chose to make himself the victim.

This is my body, broken for you.

This is my blood, shed for you.

Broken and shed to save us.

To save us from sin, to offer us redemption.

And to save us from the story we were trapped in, the story of conflict and redemptive violence, the story of us against them, they story of freedom for my people only at the expense of the other.

And to offer us instead an alternative to that story; in which

the people of God choose to stand with the victims of violence, not with those

who benefit. In which we can read the story of the Exodus and identify not with

Moses, but with the parents in Egypt grieving for the death of their child. In

which peace comes not through superior firepower, not through the exclusion of

the other, but through love, self giving, hospitality, generosity, forgiveness,

just, self-sacrifice.

For at the Last Supper, Jesus does not just reinterpret the story of the Exodus, he looks forward to a time in which that new meaning finds it’s fulfilment, in the obscure we generally skip over. He said to them, ‘I have eagerly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer; for I tell you, I will not eat it until it is fulfilled in the kingdom of God.’

The Passover, this powerful symbol of freedom, is to be fulfilled in the Kingdom of God. And until it is, he will not eat it. He has longed to share this symbolic meal with his friends, but this Passover meal is not the real thing. This Passover meal still recalls the sacrifice of a lamb and the gaining of freedom through the slaughter of the innocent.

The Passover Jesus longed to eat was the one in which the violence of the story has been drained by his self-giving, and love of enemy has replaced fear, love has replaced distrust, hospitality has replaced barriers.

The true and final fulfilment of the Passover is when the people of God are set free to be a blessing to all peoples, all nations, as the promise made to Abraham and Sarah.

The Passover will be fulfilled when all are welcome at God’s table, in the final fullness of the Kingdom of God, when God’s will for peace, love, justice, reconciliation, is done on earth as in heaven; when all God’s children are fed and clothed, healthy and educated, secure and loved.

And when humanity finally places aside the blasphemous myth that by violence against our enemy God’s will is served.

Amen