The Gate

If you look today’s reading, John 10:1-10, up in most Bibles you’ll find it under the subheading “Jesus the Good Shepherd”. And no wonder – that’s the bit of the passage that we know, that’s the famous bit, the bit which is found in a thousand works of art, countless religious images. Jesus the Good Shepherd, carrying a sheep over his shoulders, guiding and protecting his flock.

When I used to teach scripture at Wahroonga public school we were once telling this story to a year one group, and as the Good Shepherd was described to them one of the kids piped up with “the Good Shepherd sounds really nice”, to which the girl sitting next to her replied (with the confidence of a six-year old who knows the story) “Yes. That’s God. God’s always nice”

Which is, lets face it, a pretty good summary of Jesus as the good shepherd.

But maybe you noticed that those

words of Jesus, “I am the Good Shepherd”, didn’t appear in today’s reading.

They are in the next bit of John’s gospel. But today Jesus gives us a rather

less frequently reflected upon image: “I am the gate”

And I don’t know about you, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen that image reproduced in religious art. Jesus as gatekeeper, yes, standing at the gate holding it open for the sheep, but Jesus as gate?

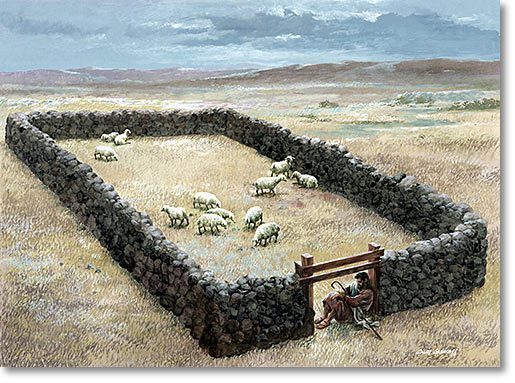

The nearest I’ve found is this

image – a stone enclosure forming a sheep-pen, with a gap in the wall; and

sitting across the gap, the figure of a shepherd. And it’s quite possible that

this is the sort of image that Jesus’ words conjured up in the minds of those who

heard him. For while the owner of a flock of sheep may have had a permanent pen

for them, with a proper gate, for the most part sheep were free to wander far

more widely to seek good pasture (on public land, as it were), and we have

archaeological evidence of these simple, low tech pens on the hillsides – walls

of rocks just high enough to serve, with an entrance around the size of a man;

pens closed not by a gate or door that would require considerably more

engineering time and effort, but by a living gate, a man sitting or even

sleeping across the entrance.

Whether or not this was the particular image that Jesus’ first hearers had in their minds, he was clearly trying to convey something of this sort of nature; that he was, himself, the one by whom they could enter, and thus be kept safe.

For that is what a gate is all about. The shepherd, sitting across the entrance to the pen, allows the sheep in, while keeping out the thieves and wild beasts who might seek to do harm to the flock.

And the experience of the early Church, for whom Jesus was speaking and to whom John was writing, was very much one of danger, of forces in the world around them that sought to destroy the movement of followers of Jesus – and to those who feel threatened, feel there are forces out there seeking to harm them, the promise of safety, of protection; the image of Jesus himself as the one lying in the gap, placing himself in harm’s way in order to keep his people in safety; that was a powerful image.

And of course, we see it too with

the hindsight of the cross; the ultimate example of Jesus placing himself into

danger in order to protect those he has called to be his people.

But there is something else in the metaphor of the gate that I think we are perhaps a little less comfortable with. Safety and protection, yes, that’s good, but a gate is more than that.

A gate works to offer that safety not just by keeping out the things that are dangerous, but by keeping the sheep (animals notoriously prone to wander off) in when they need to be kept in, keeping them in, and keeping them together.

Which is to say – the way the gate keeps the sheep safe is at least in part by exerting control over them, placing constraints upon them.

In the lectionary this gospel reading is paired with the twenty-third psalm, “The Lord is my Shepherd”, in which we find the same theme: “he leads me in right paths”, “your rod and staff” (tools used in various ways to control or redirect the straying sheep) “they comfort me”.

The image of the gate, the image of

the shepherd; they are images of safety and protection and care, but they are

also images of guidance, or, really, of control.

A gate opens and it closes. It provides safety and security, but part of the way that it works is by exerting control.

And I think we probably aren’t quite as comfortable with that image of Jesus; though we might acknowledge it, intellectually at least, I know that I for one very much prefer to focus on the language and themes of freedom – ‘where the spirit is, there is freedom’, ‘it is for freedom that Christ has set us free’ and the like.

But perhaps the last few weeks have given us another way of thinking about God’s authority, God’s direction placed on our lives, and how that sense of God’s control might interact with God’s gift of freedom.

I’m thinking, of course, about

the lockdown. That for the past however many weeks it is now, the gate of our

pens has been more or less firmly shut. Our freedom has been curtailed by an

external authority. And, of course, we are well aware, and generally accepting,

of the need, and of the fact that this constraint, this control, this reduction

of freedom, has been necessary to keep us all – individually and as a community

– safe. We look overseas at countries which were more reluctant to impose such

controls, and we’re glad that our gates have been shut.

As we look overseas we also see what happens when we only ever speak of freedom, and not of good and right and wise constraint; the slow-motion train wreck that is engulfing parts of the United States where the near-deification of personal freedom – often in the name of religious liberty – seems to have too often overwhelmed even the most basic of common sense. Sheep for whom the very existence of a gate is an offence, for whom the right of the individual to unfettered freedom of action is the ultimate good.

And I do wonder, as we look with disbelief on those protests, whether sometimes we are not guilty of the theological equivalent; that we elevate individual freedom to a height at which it does not belong.

Back at the end of March and start of April, as lockdown began, there was considerable discussion within the Uniting Church about whether the Church would authorise congregations to celebrate communion online. I was personally incredibly frustrated – I couldn’t see any good reason not to let individuals and individual congregations make the decision for themselves.

But on reflection I have to

wonder – was it such an imposition on the freedom of the individual to ask that

we wait, and take the time to consider how we might move forwards together.

For if we have learned, or been reminded, of anything through the COVID-19 lockdown it is surely this; that we can accept constraints placed upon us when we can see that they are for the common good, and are being imposed in a way that is just. Of course, we might debate the merits of any number of particulars in the lockdown, and indeed, the freedom to argue and disagree is one we have not been asked to give us, but we accept the broad principle.

For the effect of such constraint may be to reduce our personal freedom, but they actually serve to increase our freedom as a community. Sometimes we need, as individuals, to be constrained for the sake of others – especially those most vulnerable.

And so it is with the gate. For Jesus’ conclusion in today’s reading points to the deep truth; that his role as the gate, even when that role is one of constraint, serves the common good.

“I have come,” he concludes, “that they,” not you, not I, but ‘they’, ‘we’ plural “might have life, and have it abundantly”. The gate may sometimes frustrate us, may sometimes constrain us. But it serves to protect us all, and in the end to grant us greater and truer freedom.

Amen.