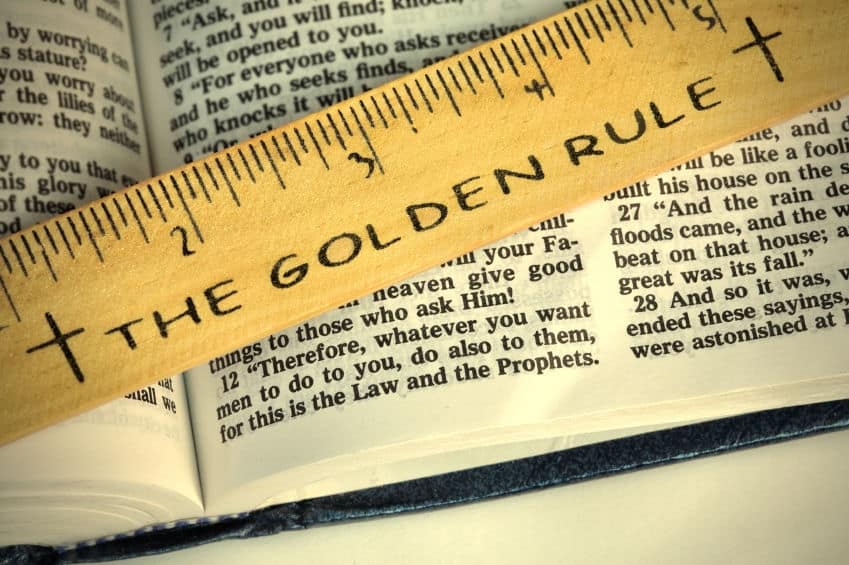

Do to others

Matthew 7:1-12

And so we come, at last, to the simple phrase that lies at the center of the ethical content of the Sermon on the Mount, and, perhaps, of the teaching of Jesus.

Two weeks ago we reflected on the Lord’s Prayer, and how it, in many ways, was the greatest possible summary of what it meant to be Christian: to identify our relationship with the Holy God as one of parent to child; or rather, parent to family; that in praying the opening few words of the Lord’s Prayer you claim that status as a member of the family of God, not as a reward or acheivment, but by simple virtue of the fact that Jesus has invited you to so pray.

I mentioned that there was a sermon in every line of the Lord’s Prayer, and indeed there is; but one way of reading the prayer as a whole is that it asks, fundamentally, for just one thing: “your Kingdom come”, refelcting the emphasis on the declaration of the Kingdom, or reign, of God in Jesus’ whole teaching. He came proclaiming that the reign of God was at hand; he taught his disciples to pray for that reign to come into reality.

Then after “Your kingdom come”, we get a one line summary of what that means, the tl;dr version: “your will be done on earth as it is in heaven”.

In heaven, we are to understand, in the presence of God, everything is shaped by God’s will, everything is in keeping with God’s will. And we are invited to pray that this will be true on earth – for that is ultimately the reality of the reign of God.

Sometimes it’s suggested that God’s will being done must mean an end to human freedom – for if we always do God’s will, so how can we have any choice any more?

I think this suggested problem rests on a misunderstanding of what “God’s will” means. It assumes that in every matter, there choice that God wants, and every other choice is therefore wrong. I don’t believe that can possibly be the case, mostly because it so obviously violates a basic principle of love: that love does not control the beloved, but sets them free.

God’s will, it’s been said, is not a narrow path, which one step to the left or the right takes you off, but a field: with edges, yes, with boundaries, but with much room to run and play.

And today, in the final words of today’s gospel reading, Jesus offers a simple summary of what the Kingdom life looks like – at least on the individual level.

In everything, do to others as you would have them do to you.

Now of course it’s frequently observed that ethical rules of this form predated Jesus. Confucious described “reciprocity” as the one word which might serve as a rule for practice for all of one’s life, and instructed “Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself”; the Greek philosopher Isocrates wrote “Do not do to others what would anger you if done to you by others.”, the Hindu writer Tiruvalluvar “Let not a man consent to do those things to another which, he knows, will cause sorrow.”

And in the book of Tobit, one of those books of Jewish wisdom that date between the end of the Old Testament and the coming of Jesus, Tobit tells his son Tobias, “what is displeasing to yourself, that do not to any other”.

But you’ve probably noticed by now that all these other ancient formulations have something in common, and differ from Jesus’ words in one crucial respect. The genius of Jesus’ simple phrase is that he, apparently for the first time, took a reciprocal prohibition – don’t do it if you wouldn’t want it done to you – and turned it into a positive, active, rule for life: do as you would be done by.

It’s a simple enough change, and, like so many truly great breakthroughs, seems obvious enough in hindsight, but it’s almost impossible to overstate what a difference it makes. The negative form existed to prevent harm, to provide a framework for legislation, a rationale for deciding what actions could be permitted, and which must be prohibited.

As such it is a huge advance on the dog eats dog, might makes right philosophies that preceeded it – and continue so often to this day – for each of the ancient philosophers I quoted took the huge step of applying their rule to all, and not just to your family, tribe, or nation; it established the universal principle that all people, whoever they are, are deserving of protection.

But turned around into positive form, the golden rule becomes not just the basis of a legal framework, not just a code to protect the weak from abuse by the powerful, but a positive, active demand for action. No longer is it simply a call to refrain from doing harm: now it is a call to arms, a challenge to action, a rule for living a life which makes a difference. That is more than just being human; that reveals the nature of God, the grace of God, to the world.

And in doing so, these simple words challenge the core of the popular understanding of sin. The Christian idea of sin is so often understood, by those within the faith as well as those outside it, in terms of the violation of a code, the breaking of rules, doing something that you should not have done.

But in the communion service that I remember from my teenage years, the prayer of confession went like this:

Almighty God, our heavenly Father,

we have sinned against you,

and against our fellow men,

in thought, and word and deed,

through ignorance, through weakness,

through our own deliberate fault

in the evil we have done,

and in the good that we have not done

The evil we have done, and the good that we have not done.

It is simply not enough, according to Jesus, to seek to avoid doing wrong, to do no harm, to cause no injury. The holy life, the life of the kingdom, is not about what we must not do – it is about what we are to do.

And it’s not like this is the only place that Jesus makes this point: in the parable of the sheep and the goats, I imagine you recall, Jesus’ condemnation of those he is rejecting is expressed entirely in terms of the things they didn’t do: I was hungry and you gave me nothing to drink, I was sick and you did not visit me, I was naked and you gave me nothing to wear. Not a word of condemnation for their actions; a torrent of it for their inaction in the face of need.

The tag line I gave to this week in our theme was “focus on how you actions affect others”. But actually, that’s not enough. We need to include a call to “focus on how your inaction affects others”.

And that’s much more of a challenge; especially for those of us who live with priviledge. Those of us who by virtue of our nation or race of birth, our education, our wealth, our gender, hold an advantage not shared by others. Because the negative: “don’t do to others what you don’t want them to do to you” allows us to live in a comfortable bubble of inaction, never hurting anyone, never breaking a rule.

Wednesday, for instance, was international women’s day. I barely even noticed – certainly didn’t do anything about it.

I’m free to ignore the gender pay gap, inequality in sexual violence, the extent to which our society depends on unpaid labour – dispropotionately that of women.

Similarly, I’m free to ignore the fact that indigenous Australians are more than ten times more likely to be in prison than non-indigenous.

I’m free to ignore the evidence that LGBTQI young people are more than four times as likely to attempt suicide than their peers.

I’m free to think that it’s ok that we expect those who can’t find work to live on an income significantly below the poverty line.

And I’m even free to think the impacts of climate change will be someone else’s problem.

Or I would be free to ignore all those things, were it not for those nagging words of Jesus.

In everything do to others as you would have them do to you.

Amen