Get out of the boat

Matthew 14:22-33

If you were here in the morning last week you’d have heard me read the story “Webster the Preacher Duck” to the kids. For those who didn’t – in the story Webster preaches an inspiring sermon to his duck congregation on God’s gift of wings, and their calling to flight. The congregation respond with enthusiasm, praising God that they have been empowered to fly – before waddling out of Church, and waddling their way back to the lake.

The story works because we recognise it. It’s easy to hear (or preach) but not be changed. Jesus’ parable of the house built on rock names this: “everyone who hears these words and acts on them will be like a wise man … and everyone who hears these words and does not act on them will be like a foolish man”.

Over the next few weeks we’re going to be looking at a series of stories from the life of Jesus as recorded in Matthew’s gospel; some miracles, some teaching, but all with a broader theme of what it means to live as disciples of Jesus. And as we look at these stories I want to hold the challenge of Webster before us, as listeners and as preachers, remembering the definition of discipleship I quoted back in January

The process of being trained incrementally in some discipline or way of life

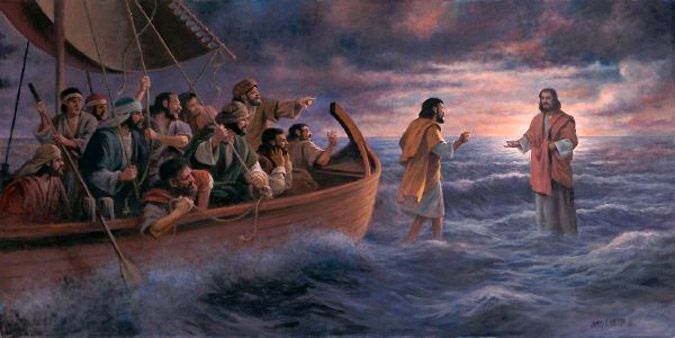

Today’s reading comes straight after the feeding of the five thousand. Jesus sends the disciples on ahead in the boat and then he dismisses the crowds.

And he went on up the mountain, to pray. And it seems he spends the night there, for it is only in the early morning that he reappears into the story.

The disciples, in the meantime, have had a rotten night; in the boat, far from land, battered by the waves, the wind against them. Presumably they haven’t slept; it’s been a long, wet, uncomfortable, unproductive night, as they struggle to keep the boat, afloat, getting tireder, watching the weather for any hint it will turn worse.

And then they see him, walking on the lake. And they were terrified.

Well, you would be, right?

They thought it was a ghost. Perhaps this reflected a superstition, common in many seafaring cultures, that those soon to drown are welcomed into the waves by those who have previously gone under.

I wonder if it occurred to Jesus, as he walked out across the lake, that his appearance would have this effect on those in the boat. Did he know how terrifying his appearance would be? At any rate, his first words – as so often seems to be the case in the Bible – were of reassurance: “don’t be afraid. Take heart! It is I”.

But all of this, Jesus walking on the water and all, is really just a prelude to the real story. The miracle here isn’t Jesus walking on water – well, I mean that is, but it’s the sort of thing that we kind of expect Jesus to be able to do, with the benefit of hindsight. But I think the lesson for disciples is what happens next:

Peter walks on water too.

I reckon the standard sermon from this point focusses on is the way that Peter walks on the water for as long as he stays focussed on Jesus, but that when he starts to focus instead on the waves and the wind, his fear returns, and he begins to sink. The miracle happens when Peter stops thinking about the problems, the barriers, the dangers, and instead simply focuses on the one who has called him; it ends when his attention returns to the troubles around him; but even then, when he cries out to Jesus, Jesus rescues him.

And that’s clearly a core message of the text. I’ve preached that sermon: perhaps even three years ago when this passage last came up in the lectionary, and we were surrounded by the storm of COVID.

But the problem with that way of telling the story is that it kind of puts the focus onto Peter’s failure to trust. Which is really a bit unfair. Because Peter is the one who got out of the boat.

In fact, I’ve noticed that we do this a lot with the disciples; perhaps because it’s reassuring to see them as having, like us, their faults and limitations. Thomas becomes doubting Thomas; Peter gets remembered for denying knowing Jesus. It’s good to know they weren’t perfect, but perhaps we sell them – and ourselves – short when we fail to give as much attention to the things they got right. And worse – much worse – I fear we do the same to other members of the Church, when we focus so much more on the things other people or groups or denominations get wrong (or that we believe they get wrong) than on the things they do which are good and right and just and true.

In any case, in this story, we sell Peter short when we focus on the reasons that he sank.

He got out of the boat. He, of all the disciples, was the one to walk on the waves with Jesus.

Wouldn’t you rather be Peter in this story than one of the other eleven?

But before he got out of the boat, he asked for Jesus to call him to do so. It was as if he knew that this was possible; that he too could do something amazing, something way outside of his personal abilities and experience – way outside anyone’s personal ability or experience – but only if he was called to do so. He believed in the miraculous, but not as something inherent to him.

This is not the story of Peter reaching within, finding the resources he needed to step out of the box, to do more than he thought he could do. This isn’t about some sort of flourishing of human capability – it’s about him hearing that word: “come”, and obeying, believing, that that word made it possible.

If Jesus called him to do it, he could do it.

And perhaps most of the disciples would be there; perhaps most of us would. If we heard Jesus call us – in whatever way we hear that call – we would have the courage to step out of our comfort, out into the unknown, to do and be more than we ever believed we would. Hearing Jesus and obeying isn’t what makes Peter unique in this story – important though listening and responding is.

What Peter did, that none of the others did, was to ask Jesus to call him.

If it is you, command me to come to you on the water

Hear the strange mixture of faith and doubt in those words? “If it is you”. This isn’t some rock-like solidity of faith (if you’ll excuse the pun which only works in Greek); he thinks in might be Jesus, but he isn’t sure.

And yet with that partial, conditional, uncertain faith, Peter asks to be called: with, as we see in the way the story pans out, the willingness to at least begin the process of obeying, if the call cones.

And I wonder if, for many of us, much of the time, just as for the other disciples in the boat, this is the step in the life of discipleship we miss? Willing to respond, to step out in faith, even onto the waves, if and when we hear the call.

A faith that is willing, but essentially reactive, where Peter’s faith was proactive. A faith that waits to be called, rather than one that seeks the call, as Peter did “command me to come to you”, or offers itself to be called, as Isaiah did when he made himself available to God “I am here. Send me!”.

As I wrote these words, I found a prayer I used when I preached on this passage in 2014, a prayer that reflects both our hesitation to be called and our sense that something else is needed. So I’d like to finish with these words, and I’d invite you to reflect on whether they ring true for you…

Lord Jesus, if it is you, call us out of our boat.

It was comfortable in here once.

But the wind and waves are against us,

And it’s a struggle even to keep going.

Call us out of our boat.

Command us to something beyond us.

Call us to you, even though the storm is raging.

Call us to follow you into something new.

If it is really you.

Amen