Economic Justice

Leviticus 25:8-17 | Luke 4:14-21

I wonder, in that video, what most grabbed you, or surprised you, or shocked you?

For me it was a statistic that I’ve heard many times before, but never fails to stop me in my tracks; that 1% of population hold 50% of world’s wealth.

Even more mind boggling is the fact that the richest eight men (and they are all men) in the world between them have more assets than the poorest half of the world – 8 men have more wealth than 3.6 billion people.

Now my grandfather had an explanation for all this. he was, shall we say, not inclined towards a left of centre view of the world. He wasn’t inclined towards a ‘paying taxes’ view of the world either, but that’s another matter.

He used to say “if at breakfastime you shared out all the money equally, before people went to bed some would be broke and some would be millionaires.”

And of course, he’s quire right.

And we see that truth reflected in our reading from the Torah today.

In the OT law it is accepted that you buy and sell from one another; that some people grow rich and others do not. Broadly speaking riches were seen as the blessing of God (although there are plenty of voices in the prophets which challenge this sort of theology of wealth – that’s a whole another topic)

But the reality of life was that a member of the community might fall on hard times; that might be their fault – through laziness or bad decisions; or it might be the luck of the draw – natural disaster, poor harvest. And another might become rich, again, by their own hard work or by luck.

And that’s not seen in the Torah as a problem.

And then, of course, the poor person may be forced to sell land, or to hire himself out in order to provide for his family. And here the vicious cycle kicks in; the man who has to work another man’s field neglects his own; the man who sells land has smaller harvests the next year; the rich become richer, and the poor poorer.

And then it kicks in through the generations; children are born into wealthy families or poor ones, and begin with all the advantages or all the disadvantages which were nothing to do with them. And the cycle continues.

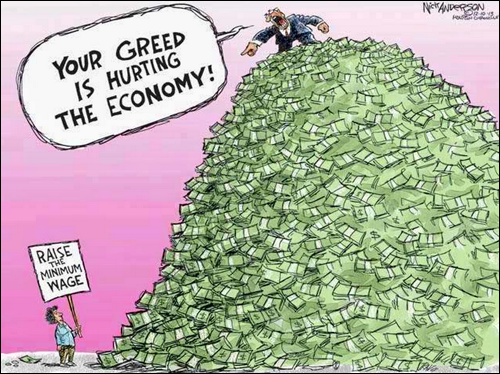

Sure, there are exceptions, the individuals who blow the family fortune or who do the ‘rags to riches’ thing; but they are very much the exception. And it gets worse, as more and more the rich get to write the rules, to control the system, to create systems and structures that exist to protect their position of privilege.

You’ve probably heard the old saying “if you give a man a fish you feed him for a day; if you teach a man to fish you feed him for life”. It’s a helpful reminder that empowering people to look after themselves is far better than trying to do it for them.

But I heard a stark rejoinder from the fisheries minister of one of the pacific states, who “We don’t need you to give us fish, and we definitely don’t need you to teach us to fish. What we need is for you to stop your super-trawlers decimating our fish stocks.”

Economic justice is just that justice, not charity. It’s not us, the wealthy generously giving a hand up to them, the poor; it’s restoring justice, accepting that we have power because of our wealth, and choosing to use that power not to protect our own privilege, but to give power back, to level the playing field.

The year of Jubilee, described in the book of Leviticus, and generally believed to be what the prophet Isaiah meant by the term “the year of the Lord’s favour” – the quote that Jesus chose to read in the synagogue to begin his Galilean ministry, was exactly that. Jubilee was a reset button; land – which was, of course one of the key sources of wealth in an agrarian society – could not be stockpiled forever. Sure, some would accumulate wealth and others would lose their land, but every 50th year the land would be returned to the family it came from. Yes, you might become poor, and you and your children might suffer; but your grandchildren would see their opportunities returned.

Isaiah declared – and Jesus quoted – that this was good news for the poor, that this was freedom for the captives and the oppressed. The year of Jubilee, of the Lord’s favour. Laid out in the law of the people of Israel as safeguard against the structural injustices that we see in our world all too clearly; the way that the rich and powerful use their positions to protect themselves and their privilege at the expense of the poor.

Unfortunately, there is no evidence in Biblical history of the people of Israel ever actually carrying out the commands recorded in Leviticus 25. What we see happening instead is just what you might expect of humanity; the rich and the powerful, David and Solomon and, even more so, the kings who came after them, fixed the rules, gamed the system. David, of course, famously sent Uriah, one of his commanders to die in battle to cover up David’s adultery with Uriah’s wife, Bathsheba, only to be confronted by the prophet Nathan; Solomon broke the laws regarding marriage to Gentiles in order to cement his political power.

The law of Moses might have set out safeguards to prevent the ever increasing concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few, but it turns out that those who have wealth are very reluctant to give it up, and far too often too powerful play by the rules.

Plus ca change

But while the problem – human nature – may not have changed, the cultural and economic setting very much has. No longer do we live in a society dominated by agriculture, nor one in which the rich and poor are mostly compatriots. In our day the issue of economic justice is international, and has al the complexities of tax law, profit shifting, tariffs and minimum wages and the international flow of capital.

Meaning that our calling as people of God is not to simply try to impose the Old Testament solutions onto the 21st century reality, but to find our way to do something to right the imbalances and injustices which arise – and from which we benefit – out of the inequality of wealth and power.

Which means, I believe, being part of the campaign to restore Australia’s international aid budget, which, as you may know, is now at it’s lowest level, as a fraction of GDP, since records began after the second world war – 0.23%. It means making sure our political leaders understand that Australian overseas aid actually makes a difference; that it works, and that we care.

And, of course, it means putting our money where our mouths are.

Back in week one of this series, when we spoke about modern slavery, I talked about how we decide to spend our money. One place we might start, as a congregation, is with our purchasing of tea and coffee – could we commit to buying fairly traded products for use in our own congregation?

And as Christmas approaches, I’d also invite you each to reflect on the fact that many people you might buy gifts for really don’t need more stuff. And perhaps you might instead buy a gift on their behalf. You’ve probably seen these sorts of cards, where you buy a three chickens for a family in Africa, and give, as a gift to your loved ones, a card, describing the contribution that has been made in their name.

I have some catalogues here, for the UnitingWorld gift cards; we’re also going to have cards from Tear available, and Sureka and Alex between them will make them both available for sale in coming weeks, after Church on Sunday, along with Christmas cards that support the work of Frontier services, who of course face some of the effects of economic injustice within Australia.

These are small steps, but steps of any size matter; to do something definite is better than any number of good resolutions. Each step is an echo of the passion of God for Justice, expressed in the law of the Jubilee and in the demands of the prophets, and echoed in the ministry of Jesus and of the Church through the ages. As we look beyond our Church and into the public arena, this is one part of showing the public face of love.

Amen