More than this

Isaiah 65:1-12 | Revelation 21:1-4

And so we come to the end of our series on the book of Isaiah, with one of the closing passages of the book; one not directly quoted by the New Testament authors, but clearly influential in their thinking.

Trito-Isaiah, the third section, is the most eclectic part of the book; containing a number of more-or-less independent pieces of writing which have led many scholars to believe that rather than the work of an individual, what we have in the final few chapters is a collection of writings by different prophets, speaking, as it were, in the school of, or in the tradition of, the original prophet. There’s a lot of scholastic debate around exactly how these sections might be pieced together, or taken apart.

But what seems clear about this chapters is that they were written after the people of Israel had returned and had rebuilt, or were rebuilding, the city and Temple of Jerusalem.

The people of God had been redeemed; returned; rescued. And as we reflected last week, part of the ongoing message of the prophet to the restored people of Jerusalem was this: God’s work of reconciliation, of bringing people into the way and realm of God, does not end with the people of Israel, or with those who fit some stereotype of ‘righteous’: God is bringing others in as well.

As if to say – this redemption that you have seen, the return to Jerusalem, the reconsecration of the Temple; this is just the start of what God is planning.

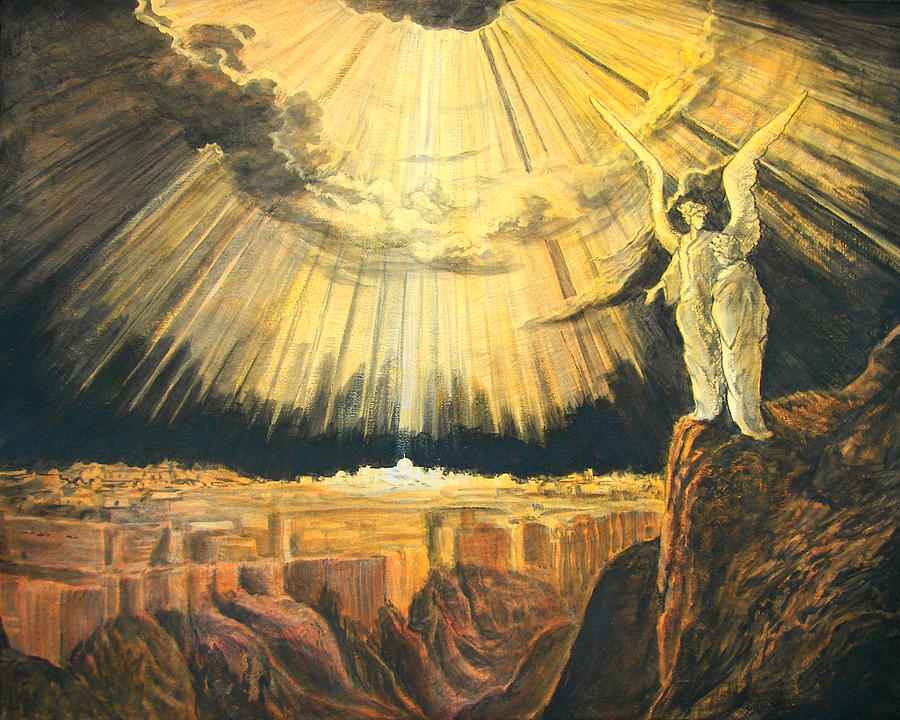

Today, as we come towards the end of the book, we read a vision of what the end of that process might look like.

Because it’s a fairly consistent characteristic of both Jewish and Christian faith – the feeling that the world is not the way it ought to be, that there is something profoundly not right with creation. In the Biblical narrative it begins with the fall, the poetic description of how it came to be that God and humanity were estranged from one another.

And the pre-fall story, the story of the garden, inspires and is echoes by the vision of the prophets old and new for how things will end. How the great story of history will finish. What the last chapter of the book will look like.

So let’s just take a moment to reflect on the fact that these words of Isaiah, these words speaking of a new heaven and a new earth, were spoken to a people who had just received the thing that they longed for: freedom, a nation restored, a religion reinstituted.

For all the years in exile the people of God had longed for this day. And now it was here.

But the words that they needed to hear were about something else; about a new heaven, and a new earth; about the end of the present things and the coming of the future.

Strange words, one might think, to speak to those who have just received everything they had been hoping and praying and longing for. Strange to then be told that all this would pass away, would be remembered no more, would be replaced by something new that God was preparing.

Or maybe not.

Because of course what they inevitably discovered, on their return to Jerusalem, was that it turned out not to be the panacea they might have thought – that the political and religious restoration that they had longed for, and had pinned their hopes on, wasn’t what they really needed.

For decades they had been told, they had told themselves, that all they needed was their freedom, was to return to the promised land, was to re-establish the kingdom; and now they had it, and yet something was still missing.

That way of thinking seems so persuasive; if only we could get back to some previous time, when things seemed better, simpler, then our problems would be solved. Back when Australia was a Christian nation, and the Sunday Schools were full. Back when everyone accepted ‘Christian values’, when we had prayer in schools, and kids read books instead of looking at screens all day.

This belief that somehow if we could just turn the clock back, regain something lost, then all would be well.

Back to when women were in the kitchen, gays in the closet, and foreigners stayed overseas. And digging up and burning coal still seemed like a good idea.

But what the people of Israel found, what pretty well anyone who ever manages to go back, finds, was that restoring the thing that was lost didn’t solve the problems. It is the tempting error of conservatism: that our glory lies in recovering what we have lost. But, as Ben Folds sang “everywhere I go, hey, there I am”: the ultimate cause of our problems goes with us, because it is us.

Not that the desire to recover that which was good but has been lost is an idea without some merits: for history is not an ever upwards march in which newer is always better; there are ideas and attitudes and ways of being which have been lost, and which we are the poorer for.

But it’s not a panacea. And, even more importantly for us, as the people of God, it’s not the vision painted by the scriptures.

Speaking to the people who have got what they thought they wanted and found it lacking, the prophet declares that there is more, far more, and better, far better, yet to come. That the feeling amongst the people that something is still wrong, something is still missing, is truth; that their restoration, wonderful and welcome though it was, is just a taster of the real thing.

And so we find, here in Isaiah, in Revelation, and in a number of other sections of the Bible, passages of so-called ‘apocalyptic’ literature. Texts which, on the surface at least, seem to describe a grand conclusion to history, a point in the future at which God will finally bring an end to all our human struggling and institute the complete and permanent rule of God.

But for a number of reasons, I don’t personally read these words – here in Isaiah, or in Revelation, or elsewhere – as speaking of a final, history ending event, a second coming. I don’t read them as saying that on some unknown date in the future, God will sweep away the old heavens and earth and replace them with a new creation. Now don’t get me wrong – that is a perfectly reasonable way to read these texts, it was certainly the expectation of the early Church. But two thousand years on and still waiting, it’s not the interpretation I find most convincing.

Instead in these words I see God’s vision-casting: God describing the world as God dreams for it to be. A world in which there is no longer pain or weeping, a world in which there is no violence, a world of stability, security, justice, a world of joy and delight, a world where God’s presence is real and known and experienced, where the wolf and the lamb feed together, where those who once lived in fear of one another now live in partnership.

It seems to me that the prophet, in describing this vision of God’s new creation to the restored people of God is saying: “The nation you longed to recreate, the Temple you longed to rebuild, the land you longed to return to; these are all good things. But in the end all of those things will always fall short of what the world is truly supposed to be like.”

But if the tempting error of conservatism is to believe that the best version of the world lies in human constructs of the past, then the tempting error of progressives is to believe that it lies in human constructs that we are yet to create.

For the classic characteristic of all apocalyptic literature is that it describes the dramatic, history shaping work of God. Work done through human agency, yes, but work of which humanity is not the prime agent. Work that we, in the light of the revelation of God in Jesus would say has been done, is being done, and will be done, in the redeeming work of God in Christ, and by God’s Spirit, through the growth and advance of the Kingdom of God.

Apocalyptic literature paints a vision of how the world should be, how the world could be, and then offers us a promise: by the will and work of God, this is how the world will be.

Throughout the book of Isaiah words of challenge and critique have been mixed with words of hope and promise. And so it is that we leave Isaiah with words which are both of hope and of calling; a hope and calling echoed in the gospel of Jesus, in the words of the Kingdom, and in the apocalypse of revelation.

The Christian hope: that the image of how God dreams the world should be will come into reality.

And the Christian calling: to play our part in sharing that dream and filling in the colours that God has outlined .

Amen