Walking in the Light

Isaiah 2:1-5

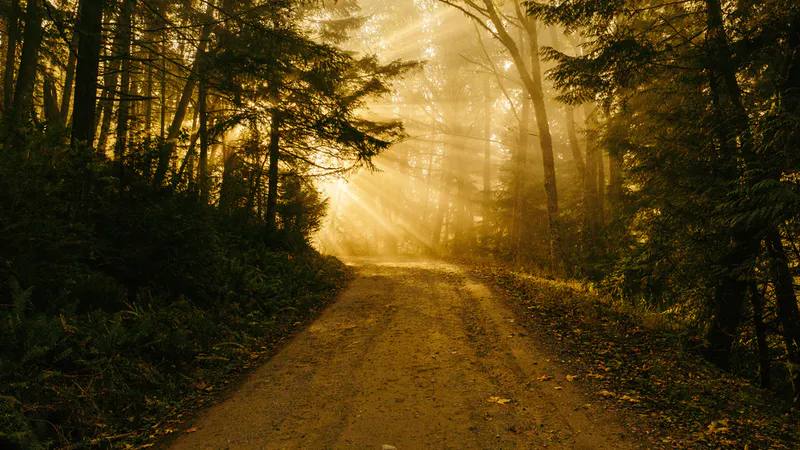

There’s a saying, attributed to the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu, that “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step”. But in truth, many journeys begin long before your feet touch the road.

You know this from planning for a trip, or a holiday – the journey begins not with your feet, but in your mind, in your imagination. It begins with an idea, a dream, a hope, a longing to go, to see, to discover, to experience.

Long before you leave your home to begin the physical journey, you’ve might have made it many times in planning, in imagining, in expectation.

This year our theme for advent is the Christmas Journey – the journey that we each make every year through the weeks before Christmas, the journey that leads us up to celebration of the birth of Jesus, Emmanuel, God with us.

Every year the month of advent takes us on this journey, this time of preparation. But this year advent comes at the end of a year which has already been a much stranger journey than most.

This time last year, the news was completely full of a national tragedy, as bushfires swept the Eastern coast of Australia. As we looked towards the end of 2019 and the start of 2020, we were looking more than anything for rain, for an end to heat and dry and smoke haze that filled the air.

And early in 2020 the rain came, and we celebrated, and looked forward to the rest of the year, with no idea what awaited us.

We didn’t know what the path ahead of us held in store. And, of course, we still don’t. However much we look forward to 2021, even if it is simply because it isn’t going to be 2020 any more, we don’t know what the next year of our journey will bring to us.

There are, of course, some things we might be looking forward to with hope and a certain degree of reasonable expectation. The reopening of borders across Australia. The end of the Trump presidency and with it, perhaps, perhaps, more constructive international engagement, especially on climate change. The availability of a vaccine, and all the new opportunities that might come with that.

More tentatively, we might as a nation hope that 2021 will bring an economic recovery, and in particular, that the many, many people, especially young people, who have lost their jobs in the COVID recession will be able to find meaningful and rewarding work in the year to come.

But as we look towards 2021, we know that we’re probably also going to see some pretty rubbish things happen, or continue to happen, as well.

Despite some signs of hope, we still, as a global community, seem stubbornly set on a path towards environmental catastrophe.

It seems likely that our short term willingness to provide support those looking for work will come to an end, and we will return to expecting job seekers to survive on income below the poverty line.

And there seems even less hope for a change in attitude towards refugees and asylum seekers, those most vulnerable of people, disproportionately impacted by COVID and demonised by the cheap nationalism that seems to be on the rise in so many nations.

And who knows what surprises 2021 might have in store on top of all that.

So how do we read the journey of advent, the journey towards Bethlehem, this year?

I began by saying that the journey of a thousand miles starts not with the first step, but with something before it. The advent journey, the Bethlehem journey, starts with an idea, with words of prophecy pointing towards a time to come.

And, perhaps most crucially for us, in our strange times, the advent journey starts with words of hope.

In days to come the mountain of the LORD’s house shall be established as the highest of the mountains, and shall be raised above the hills; all the nations shall stream to it

Shall be.

Shall be established.

Shall be raised.

All the nations shall stream to it.

There’s an incredible sense of confidence, of certainty, in these words. In Hebrew, it’s even strong – I’ve mentioned before that one of the weird things about the Hebrew language is that it doesn’t do tenses, past, present, future, like we do – it just has two, essentially ‘finished’ and ‘not finished’.

The words from Isaiah 2 here are set into the future by the context – “In days to come” – but then they are declared in the “finished” tense, as if they were incontestable historical facts. “In days to come, the mountain of the LORD’s house has been established… has been raised”

It’s the way the prophets often speak of the things of God. Though in our journey, our timeline, they may still be in the future, they have been declared by God, they are as certain and reliable as if they had already come to pass.

I have spoken.

So the prophetic words of hope are not some vague, fuzzy, sense that maybe things will get better in the future: they are an absolute declaration that this is God’s intent, and it is therefore a certainty upon which one can rely.

But at the same time, the words of the prophets aren’t, as a general rule, very specific. Certainly not about timeframes, or particular details of how the promise will come to be.

Now some Christians would disagree on that point, arguing that if you read the Bible carefully enough, you find that it speaks very specifically to the present day. I’ve been quite seriously told in the last week that the Bible clearly states that the COVID-19 vaccine is the mark of the beast and will modify your DNA to make it so you can no longer believe in God.

Without going down that particular rabbit hole, suffice to say I don’t think that’s how Biblical prophecy works.

What the prophets do, in a very broad sense, is two things: they declare the things that are important to God, the things that ultimately matter; and they assert that despite all appearances, those things of God are the final destination of creation.

As the old hymn puts it: “God is love, so love for ever o’er the universe shall reign”.

The future is not certain – 2021 may hold just as many surprises as 2019 and 2020 did. And the Bible doesn’t change that, and Biblical prophecy doesn’t give us any deep insights into what the year ahead will hold.

But the prophets declare the heart of God, the values of the Kingdom, and then assert that however it looks in the meantime, that heart, those values, describe how things will come to be.

And so we live as a people of a strange kind of hope. A hope that is neither vague nor specific, but a promise; the same sort of promise that you usually find implied by a novel, by a story – the path might be twisted, but the end will be right, will be a resolution, will be happy. You know that Elizabeth will marry Mr Darcy, even as the plot twists; you know the ring will be destroyed, Voldemort will be defeated. You don’t know the details, but you do know the vibe – you don’t need to skip ahead and read the last chapter.

That is the sort of hope that Biblical prophecy, and words like these of Isaiah offer to us. Not of knowing the way the road will take us, but of confidence in what the destination will look like.

As so it is that Isaiah can offer words of hope, a promise of redemption, even in the dark times that the people of God are walking in. And so it is too that those words of hope, of promise, naturally lead into the challenge with which our reading today ended:

O house of Jacob,

come, let us walk

in the light of the Lord!

The prophet has described what the light of the Lord looks like, what the reality that God is in the process of creating, and has promised will one day be fulfilled, is and will be like.

So walk, the prophet entreats is, in that light.

Hold onto that promise, that you know the way the story will end, and so commit yourself to living it into reality. Be the change that God has promised.

Walk in the way of the light with confidence that you are on the right side of history. Fight for causes which seem hopeless because they are not – because even when justice seems far away, God promises that it is coming, and if you are the side of justice, you will find that you were on the right side of history.

2021 will bring its share of challenges and injustices; our call is to walk in the light. As we, as a nation and a world seek to build a new normal, our call is to be the hands and feet and voices standing and working and speaking for a new justice – for the rejection of cultural norms that accept domestic violence, that trivialise rape, that stigmatise neurodiversity, that marginalise faith; of political norms that tolerate corruption and entrench privilege; of international norms that accept violence and neglect the environment.

Not because these things are easy, but because God has told us the way things will be, and we might as well be working for the right side.

Amen