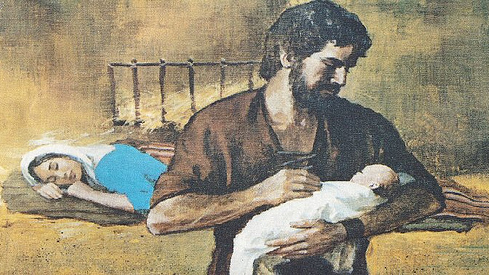

Joseph

Matthew 1:18-25

We don’t hear very much about Joseph in the Christmas story.

In fact, we don’t hear very much about Joseph at all in the Bible. Sometimes this is taken as an indication that he had died before Jesus began his public ministry, as an explaination of the fact that while Mary, his mother, comes up several times during the life and ministry of Jesus, Joseph disappears from the scene. Perhaps so – or perhaps it just reflects the fact that Joseph was not as free, in some ways, as Mary, once their oldest child had grown. He still had his trade, probably still had other children to provide for. The patriarchal system that he lived in gave men a great deal more power than women; but for an honourable man, who takes his responsibilities seriously, that power also entailed responsibilities.

There’s been a post – a meme, even – doing the rounds on Facebook, in the sort of circles that I see, this year. It reads “When male pastors call on us to recover something called “biblical manhood” I suspect they’re not thinking of the silent, loyal Joseph submitting himself humbly to his wife’s God-given calling.”.

But back to what we are told of Joseph in Matthew’s account.

Joseph, we are told, was a righteous man: he was unwilling to disgrace Mary even when she was found to be pregnant during their engagement. Although there does seem to be something of a failure in Joseph’s logic: if he broke off the engagement, and Mary went on to have the child, unmarried, what did he think would happen to her? His plan to dismiss her quietly might save her from immediate disgrace, but maybe he just didn’t think it through. Breaking off the engagement, in truth, would serve him better than it would serve her, avoiding the natural conclusions that the people of Nazareth would draw if they went on to marry, and then Mary had a child rather too soon after the wedding.

So Matthew’s desription of Joseph as “righteous” seems a little generous to me. At very least, it seems to me, it sees things through a very male lens.

And as we notice that, perhaps we also reflect on the fact that Matthew gives us the story very much from the perspective of the men.

In Luke we have the angel coming to Mary, we have her questioning this messenger of God before accepting her role in the play; we have the magnificat, we have the story Mary and Elizabeth.

In Matthew, on the other hand, the angel gives the news that this child is of the Holy Spirit to Joseph; and later, when Herod commands the slaughter of the innocents it is to Joseph that an angel will appear, to tell him to take Mary and the child and flee to Egypt.

For Matthew, Joseph is the one who matters.

And it’s tempting at this point to conclude that this is Matthew failing to overcome his own instinctive and cultural sense that this story – like any important story – revolves around the men in it. Or perhaps one might be a little more generous and say that Matthew, writing for his mostly Jewish audience, emphasises the role of the father because he knows that that is what his readers will expect, and that a story which gives emphasis to the role of women is less likely to be heard and accepted.

But to come to such a conclusion is probably unfair on Matthew. For it is Matthew who gives us the names of some very interesting women in his genealogy; at the end of his story, in the narrative of the resurrection, he gives us the men dispersed, and the women witnessing the burial, and, of course, being the first witnesses of the resurrection. Uniquely, in Matthew’s gospel none of the men go to the tomb to see for themselves.

This isn’t the narrative of an author who only considers men to be important characters.

I think that Matthew’s emphasis on the role of Joseph comes from a different place. For Matthew there was something far more important about Joseph than his gender; and that was his lineage. That he was a descendent of David.

The title “Son of David” was an important one to Matthew, and to his Jewish readers. He uses the phrase ten times in the gospel; the other three use it only six times between them.

Matthew begins his gospel “An account of the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah, the son of David”. The angel addresses Joseph as “Joseph, son of David”. Blind men cry to Jesus “have mercy on us, son of David”; the crowds wonder “could this be the son of David?”; and later, as he enters Jerusalem, they cry out in praise “Hosanna to the son of David”.

Both of the genealogies that we have in the gospels, interestingly different though they are, trace the line of descent from David to Joseph. In Luke 2, we read that Mary and Joseph travelled to Bethlehem “because he was descended from the house and family of David”.

If Mary, too, was a descendant of that house, we have no indication of it. Luke, emphasising the role of Mary, gives us no mention of her father as, son of, son of, son of, son of David.

But Joseph was a descendent of David. And that was really important to Matthew, and indeed, to the early Church.

Because it was this that made the connection between all that had gone before and all that was to come. All the quotations of the prophets, all the talk of messiah, of the one that God had sent, the one who would be the light in the darkness, who would be the good shepherd, who would usher in that reign of God in which swords would be beaten into plowshares, all of this depended, as Matthew and his contemporaries understood it, on the title “Son of David”.

Throughout the gospel, Matthew will draw upon the tradition of his people, will take the words of the prophets and declare them fulfilled in the life of Jesus.

And we do the same. In the past few months we’ve read the words of the prophets, the promise that even in times when everything is changed, we are still the people of God, that there is yet a future with God for us, and we’ve taken hold of them as an inheritance, as applying to us just as fully as they did to the people who first heard them, thousands of years ago.

We draw these pieces of the Hebrew faith into our own understanding of who we are, and how we stand before our God, into our own understanding of Jesus. We’ve done it for so long, and taken the Hebrew prophets so deeply into our faith that we don’t even realise we’re doing it, or why.

But it’s because of Matthew. And because of Joseph.

A man who was prepared to trust the message of the angel; to be the human father Jesus needed; to do what he needed to do to keep his new family safe; to take a supporting role and then simply disappear.

To be a Son of David, but not the one that everyone would talk about. Joseph gets none of the glory, but it wouldn’t have been possible without him. How often is that the way for us?

So this year, let’s give a little bit of our Christmas attention to Joseph.

Amen