Hebrews 9

Hebrews 7:11-14

We come today to one of the more difficult bits in the book of Hebrews; difficult both because it is more alien to us, and because of the traditions of the Jewish faith that it alludes to.

I love the book of Hebrews for the way that it takes a deep and complex religious tradition and, as it were, mines it for the truths about God which are meaningful, eternal, just as we look at our own traditions of faith and ask “what is the truth of God that we are drawing on in this part of our liturgy, this part of our practice”.

But this passage requires a bit more work of us; and I think it’s probably shown itself to be more harmful when we don’t do that carefully.

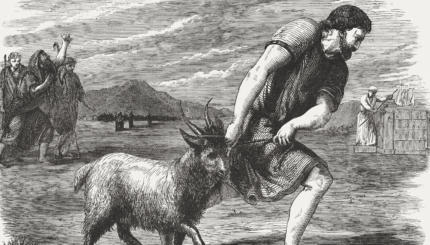

Because this bit of the book of Hebrews is about the sacrificial system; the blood sacrifice of animals in the Temple as part of the religious observance of the Jewish people.

In the last couple of weeks, we’ve seen the author show how Jesus fulfils all the good and true aspects of the Hebrew faith that were represented for them in role of the Priesthood; now she or he turns to the role of the sacrifice.

And this is difficult, because it plays into a theological description of the death of Jesus called Substitutionary Atonement. That’s the idea that because God is holy, sin requires punishment. And so God, being also loving, allows that punishment to fall upon a substitute – the sacrifice made on our behalf. First, the blood of sheep and goats; then the blood of Jesus.

And while this way of understanding the death of Jesus can be read in some passages of the New Testament – such as the one we heard today – and therefore has something to say to us about the nature of our salvation, I believe it is deeply problematic when it is elevated to being the one true description of how we are saved (and from what).

For when we elevate the sacrificial system and the substitutionary role of Jesus what we say some things about God which are profoundly contradicted by both the wider scriptures and by Jesus himself.

For this way of talking requires that we cast God in the role of the angry one, the one who must punish someone, but who is prepared to see that punishment fall on a sacrifice instead of the guilty party.

How is this an image of justice? To say there must be punishment, but it doesn’t matter who is punished, as long as they are willing to accept it (a choice Jesus had, but of course, the goats didn’t)? Would we consider it an improvement to our justice system if we allowed a volunteer to serve prison time instead of the convicted criminal?

Or what of our language of God as parent? Do we hold to a view of parenting that says wrongdoing must be punished; that if a child is obviously sorry for something they’ve done, they need to be punished anyway, in order that the demands of justice be met?

It’s been said that Substitutionary Atonement asks you to look at the crucifixion and see God primarily in the soldier driving the nails into Jesus’ wrists, in Pilate condemning him to death, in the crowds shouting ‘crucify’. To see God in the corrupt system that kills the innocent to protect the powerful.

That’s where we end up if we take the superficial trappings – the sacrificial system – as being the core truth, rather than looking for what lay behind that system that was of profound eternal value.

Just as the writer of the book of Hebrews looked at what was genuinely meaningful in the Priesthood, not in order to preserve the Priesthood, but actually in order to do away with it, by showing that everything good that it brought to the table was met, and bettered, in Jesus.

So here the author would do the same of sacrifice. Not to preserve it, but to abolish it (or, in Jesus’ own words, to fulfill it).

That’s the whole task of the book of Hebrews – making sense of the Hebrew religious tradition – drawing out the truth embedded within the formalities.

And I think it’s really important to note that this wasn’t something new. This wasn’t an invention on the part of the author. The idea that the sacrificial system wasn’t the truth, but was a representation of that truth, arises in the Hebrews prophets.

In Amos 5:

I hate, I despise your festivals,

and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies.

Even though you offer me your burnt-offerings and grain-offerings,

I will not accept them;

and the offerings of well-being of your fatted animals

I will not look upon.

Take away from me the noise of your songs;

I will not listen to the melody of your harps.

But let justice roll down like waters,

and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.

The truth is not the sacrifices of fatted animals, but the sacrificial life, the life of justice and righteousness. The sacrificial system means nothing in the absence of justice.

Or in Isaiah 1

What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices?

says the Lord;

I have had enough of burnt-offerings of rams

and the fat of fed beasts;

I do not delight in the blood of bulls,

or of lambs, or of goats.

Before continuing:

seek justice,

rescue the oppressed,

defend the orphan,

plead for the widow.

Come now, let us argue it out,

says the Lord:

though your sins are like scarlet,

they shall be like snow;

though they are red like crimson,

they shall become like wool.

The truth is not the burnt-offerings, but the offer of God’s forgiveness; even as God rejects the sacrifices, God offers forgiveness.

It could not be clearer that God’s forgiveness does not depend upon the sacrifice, but upon the life of repentance.

Or in the gospel reading set for today, in which a teacher of the law asks Jesus what the most important commandment it, and Jesus replies with the famous “love God, love your neighbour” formulation. And the scribe responds

to love one’s neighbour as oneself”,—this is much more important than all whole burnt-offerings and sacrifices.’

The truth is already there in the Hebrew tradition. And Jesus’ response affirms it:

When Jesus saw that he answered wisely, he said to him, ‘You are not far from the kingdom of God.’

The sense that sacrifical offerings were an outward representation of the people’s relationship with God, of the truth of God’s declaration “I will be your God and you will be my people” was there in the traditions of the Jewish people.

Which, of course, is why Judaism today doesn’t rely of animal sacrifices…

So what is the underlying truth that the sacrificial system, problematic though it might be, points us towards?

I think that if you read through the descriptions of the laws around sacrifice there are three things that really stand out (for me, at least).

The first is that the system recognises the reality of sin. That’s something that we in the less fundamentalist parts of the Church sometimes shy away from – the reality that sin is a reality. It’s a reality in our structures that encourage greed, reward selfishness, turn a blind eye to violence, and it’s a reality in our personal lives. Sin, the sacrificial system insists, is real, and it matters. We fail to love neighbour, to live justly.

And flowing from that is the reality of consequences. When we do wrong, or when our social, political, economic systems are sinful, people get hurt. I was reading this week about oil companies internal documents predicting the catastrophic effects of climate change in the early 1960’s – 60 years ago, before I was born – but choosing to bury that information in order that profitable business as usual could continue. We, and future generations, face genuine consequences of that systemic sin.

And of course we know all too well that when we do wrong, others get hurt. Often those closest to us.

And that, perhaps, leads to the third thing: that we have (at our best) a deep need to make good, to ‘do something to fix it’ when we realise we are in the wrong. We know that somehow it often isn’t enough just to say ‘sorry’, we need to do something about it. It’s the wisdom behind the Catholic practice of penance: not that God needs us to do something in order to forgive us, but that we need to do something in order to be able to accept that forgiveness.

The sacrificial system captured those truths. That sin is real. That is has consequences. And that we need to be able to do something to make it right.

And those are exactly the same truths that the prophets were insisting on when they condemned a sacrificial system that had become focussed on the external and not on the underlying truth; Amos and Isaiah both insisting that sacrifices mean nothing if they are not about repentance, and the correction of injustice.

And it is, to bring this around to a close, these truths that Jesus captures and fulfills.

For he died, quite literally, without a hint of metaphor, Jesus died because of sin. He was innocent but he was executed because people were threatened by him and they were willing to kill to protect their ways.

Sin is real. Personal and structural. And it has consequences. Jesus’ death demonstrated them. There is no theological gloss here: Jesus’ death demonstrated, and accepted the reality of, the consequences of sin.

And, the author of the letter insists, Jesus also offers the way to make it right. That what he did “obtained for us eternal redemption… purifing our conscience from dead works to worship the living God”.

And in those last words, the author shifts our desire to make right. Away from dead works, and to the worship of the living God.

The first Jewish believers knew that sin mattered, and wanted to do something about it – as everyone who is awake to the consequences of their actions does.

And the author of the letter to the Hebrews redirects that desire: no longer is it to be satisfied by sacrifices – dead works – for Jesus has fulfilled that system. Now instead, it is satisfied by the worship of the living God.

Just as Amos did. Just as Isaiah did. The author of the letter the Hebrews declares that it is not the symbol of sacrifice that matters, but the life lived in worship.

The sacrificial system, and all that is pointed to, has been fulfilled. Jesus’ life and death and resurrection is enough.

What remains to us is the response of a life of worship. Worship that, as the prophets insisted, is made known in works of justice; that as Jesus declared, is seen in love of God and of neighbour.

Amen